July 22nd, 2019 was Bhakti Adhyaksa Day, the birthday of the Indonesian Public Prosecutor’s Office. The vision of the Public Prosecutor’s Office is to be ” a professional, proportional and accountable law enforcement institution”. On this Bhakti Adhyaksa Day, the Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation (YLBHI) and 15 LBH offices present 20 facts (attached below) demonstrating that the Public Prosecutor’s Office is far from professional, proportional and accountable, and has failed to prioritise democracy and human rights in carrying out its duties. YLBHI has identified at least seven serious concerns with the Public Prosecutor’s Office, as follows:

- The Public Prosecutor’s Office is not yet professional and does not uphold the right to a fair trial in carrying out its duties

In the criminal justice system, the public prosecutor should be the controller of a case (dominus litis). As such, case investigations conducted by investigators (including police), must be fully supervised and controlled by the public prosecutor. This is because the Public Prosecutor’s Office is responsible for verification of evidence, as well as prosecution in the courtroom. Although the criminal justice system provides for it under Article 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code (KUHAP), the Public Prosecutor’s Office rarely uses its authority to return case files with insufficient evidence to police or not continuing with prosecution.

- The Public Prosecutor’s Office is discriminatory and violates human rights

Under Article 30(3)(d) of Law of No. 16 of 2004, the Public Prosecutor’s Office is provided with the authority to monitor religious beliefs “that can endanger the state and society”, through the Coordinating Agency for the Monitoring of Beliefs in Society (Bakor Pakem). This body has discriminated against religious minority groups. The inclusion of non-state actors such as religious institutions in the body has seen it become increasingly unaccountable.

- The Public Prosecutor’s Office role in monitoring ideology damages our democracy and violates human rights

One of the functions of the Public Prosecutor’s Office is to oversee ideology in society in the name of peace and public order. Freedom of thought and expression is guaranteed by the Constitution, Law No. 39 of 1999 on Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which was ratified into Indonesian law through Law No. 12 of 2005.

- The Public Prosecutor’s Office has hampered the resolution of human rights violations and acts as an instrument of impunity

According to Law No. 26 of 2000 on the Human Rights Court, the Public Prosecutor’s Office is provided with the authority to investigate human rights violations, while the National Commission on Human Rights is only responsible for preliminary investigations. According to the KUHAP, the task of investigators is “to search for and collect evidence that clarifies [the details of] the crime that occurred and to identify the suspect”. In reality, the Public Prosecutor’s Office always refuses to investigate human rights cases, and returns case files to Komnas HAM, claiming insufficient evidence. Despite the fact that it has responsibility for collecting evidence itself.

- The Public Prosecutors’ Office has the potential to cover up disclosures of corruption

The Public Prosecutor’s Office established the Team for the Monitoring and Security of Government and Development (TP4), which was strengthened byPublic Prosecutor’s Office Regulation No. Per-014/A/JA/11/2016 on mechanisms for its technical and administrative work. In practice, this team has the potential to limit the disclosure of corruption in the projects it monitors, and even provide opportunities for corruption itself.

- The Public Prosecutor’s Office is not independent

The Public Prosecutor’s Office has adopted a system in which the supervisor has the authority to determine the charge and indictment, not the prosecutor who attends the court and is aware of the facts of the trial. The prosecutor must submit the indictment plan (Rentut) and submit it to his or her superior at the relevant district, provincial or national level. This system means that the supervisor can put pressure on the prosecutor, and leaves open the possibility for gratification, trading influence, bribery and extortion.

- The Public Prosecutor’s Office is not transparent

Access to information in the Public Prosecutor’s Office is relatively closed. It is difficult for the public to access information, including the circulars or directives produced by the Office, which can have significant implications for the community.

Jakarta, July 21, 2019

YLBHI-LBH

(LBH Banda Aceh, LBH Medan, LBH Padang, LBH Pekanbaru, LBH Palembang, LBH Bandar Lampung, LBH Jakarta, LBH Bandung, LBH Semarang, LBH Yogyakarta, LBH Surabaya, LBH Bali, LBH Makassar, LBH Makassar, LBH Manado, LBH Papua)

C.p

Asfinawati 0812 8218930

Era 0812 10322745

Appendix: 20 Findings About the Performance of the Public Prosecutor’s Office

- Public prosecutors are not using their authority as case controllers (dominus litis) to stop cases of criminalization that originate from police investigators for progressing to trial. Prosecutors instead follow the “rhythm” of police investigators and force these cases into court.

- Prosecutors keep continuing prosecution process even when there are indications that evidences in the criminal cases are obtained by police through torture.

- As the executor of court decisions, prosecutors are reluctant to do so and delay releasing prisoners. As a result, prisoners or convicts are detained or imprisoned for excessive periods both in detention centers and correctional institutions.

- Prosecutors frequently issue detention orders for suspects at second stage of the process without clear reason, even when suspects are cooperative and have not been detained during the investigation phase.

- Prosecutors do not provide letters of extension of detention to defendants

- Prosecutors are irresponsible on cases they handle. The prosecutors who responsible for handling the cases does not attend court, and send a different prosecutor in his or her place, which slows down the trial procedure.

- Prosecutors often forget to bring certain suspects or evidence to trial, meaning that charges are difficult to prove.

- Prosecutors only accept suspects during the delegation stage (P22), but case files are not received.

- Prosecutors often make errors in the execution of court decisions concerning evidence. For example, a court may order for evidence to be returned to the victim but it is instead returned to the defendant.

- When attending the trial, prosecutors often do not wear a full uniform. For example, they may wear sandals, or not wear court robes, which affects the authority of the court.

- Prosecutors may request defendants to revoke the power of attorney that has been given to LBH or their lawyer.

- Prosecutors ask defendants for money in return for promises, such as a reduced sentence demand in court.

- Prosecutors will often not inform the defendant and his or her legal representative about the agenda for the first instance trial despite knowing that the defendant has appointed a legal representative.

- Prosecutors often try to buy time to present witnesses and victims, then ask the panel of judges to simply read the victims’ investigation reports (BAP). This strategy is used to avoid revealing the weakness of their indictments and the cross-examination of witnesses.

- Legal uncertainty and undue delays caused by cases being passed back and forth between prosecutors and police. Public Prosecutor’s Office Directive No. PER-036/A/JA/09/2011 on Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for Handling Criminal Acts states that cases files can only be passed twice between investigators and prosecutors. In practice, this circular is not enforced. There are many cases in which the file has been passed between investigators and prosecutors several times, disadvantaging victims.

- In routine cases, such as criminal cases that do not attract significant media attention, criminalization cases, and cases involving poor defendants often attract high sentencing demands. This is because sentencing demands are determined by the chief prosecutor and not by the prosecutor who is in charge of handling the case, and is more aware of the facts.

- Public prosecutors appeal against criminalization cases or those involving the poor because they feel they have an obligation to do so. This occurs even in situations where the facts revealed during the trial have demonstrated that the indictment is weak or there is a reason to not pursue criminal charges, for example in some cases involving indigenous peoples. In fact, prosecutors’ obligation to appeal when the judge’s decision is less than 2/3 of the sentencing demand (described in Public Prosecutor’s Office Directive No. SE-013/A/JA/12/2011) has been revised by Public Prosecutor’s Office Directive No. B-3841/E/Ejp/12/2012, which states that local wisdom, restorative justice, and diversion should also be considerations.

- Prosecutors often appeal acquittals. Article 224 of the Criminal Procedure Code (KUHAP) states that acquittals cannot be appealed, but prosecutors continue to do so. This violates the defendant’s rights and damages legal certainty.

- Prosecutors do not provide case files voluntarily. Case files are vital for defendants and their legal representative to prepare their defense. Yet prosecutors often do not provide documents until legal representatives request them in front of judges.

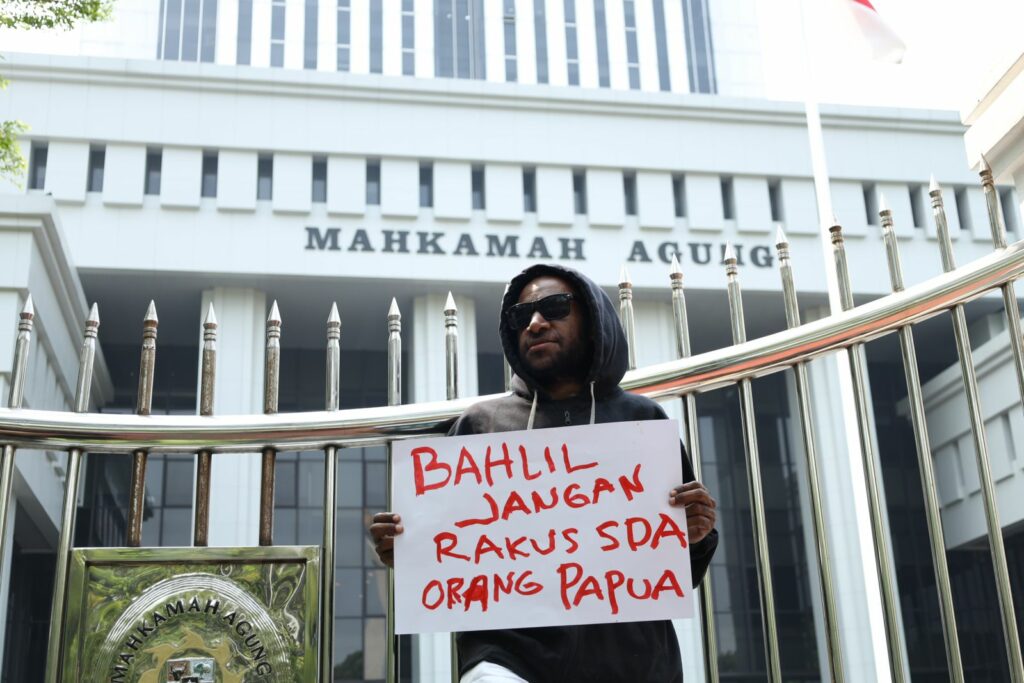

- Prosecutors discriminate against indigenous peoples. Although Public Prosecutor’s Office Directive No. B-230/E/Ejp/01/2013 asks prosecutors not to be rash in prosecuting defendants in cases involving land because such cases may often by civil cases, in practice, indigenous communities are often asked to produce certificates proving land ownership. This is despite the fact that most indigenous communities do not have certificates to prove ownership over their customary land.